|

There are major changes coming to jury selection in 2019. Below, we've kept information on the old system. But here is a quick guide to the 2019 changes.

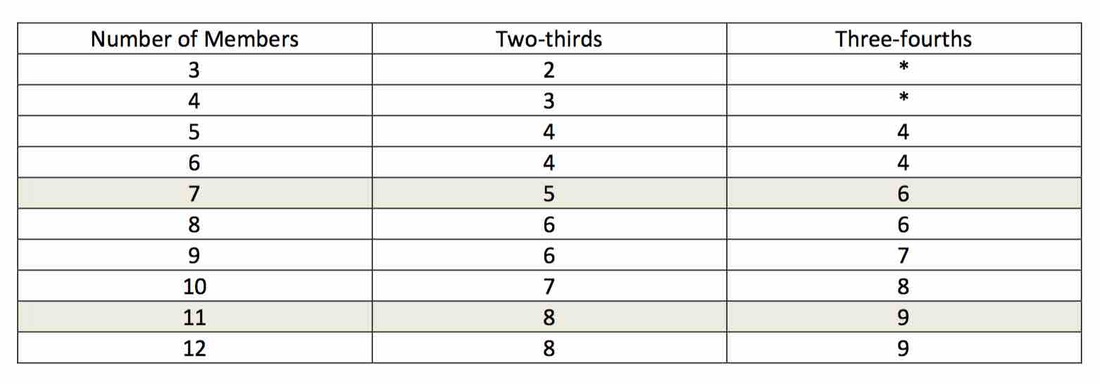

Here are the major changes to military practice for 2019. This is a very simplified guide to give potential accused members a general idea of the changes coming for 2019. Court-Martial Composition In 2019, court-martials will have a fixed composition. A General Court-Martial will have 8 members. It could be reduced to 6 or 7 after challenges or excusals. In capital cases, the jury will have 12 members. In a Special Court-Martial, the jury will consist of 4 members. There is a new type of Special Court-Martial that is military judge alone. How Does Voting Work Under the new system, a conviction will require a 3/4thvote (75%). A General Court-Martial with 8 members will require 6 votes to convict – 3 votes to acquit. A Special Court-Martial with members will require 3 votes to convict – 2 votes to acquit. How Will Military Judge Alone Special Court-Martials Work Under the new system, a military judge alone special court-martial will have certain sentence limitations. The judge will not be able to impose a punitive discharge, confinement for more than 6 months, or forfeitures of pay for more than 6 months. Enlisted Members from the Same Unit as the Accused Article 25, UCMJ was updated. Previously, enlisted members from the same unit as the accused were prohibited from serving on a jury. Now, any enlisted member is eligible to serve – including from the same unit. Alternate Members The new Rule for Courts-Martial 502 (a)(2)(B) and 912 allows the Convening Authority to detail alternate members to a court-martial. They are present and hear evidence, but do not participate in deliberations. Are there new Sentencing Rules Under the new system, a military judge will conduct all sentencing. In a members case, the accused can elect sentencing by members. With members sentencing, the jury will adjudge a single sentence for all offenses. With military judge sentencing, the judge will determine appropriate terms of confinement and/or fines for each specification. The judge then determines whether the sentences are concurrent or consecutive. Terms of confinement for two or more specifications will run concurrently when they involve the same victim. In the military system, jury selection is unique. The jury is called a panel. The Court Martial Convening Authority (CA) selects the panel from a pool of available members of the command. The CA has wide discretion in selecting the members of the jury pool. All the panel members must be senior in rank (date of rank) to the accused, but the selection is not random. In a special court-martial, the jury must be composed of at least three members. In a general court-martial the minimum size is five. Most jury pools start with 10-12 members for jury selection - this includes special courts-martial. Enlisted members have a right to a panel composed of at least 1/3 enlisted members. A guilty finding requires a 2/3 vote. A voting chart is included below. Percentages are always rounded up in favor of the accused. Defense counsel has 1 peremptory challenge and unlimited challenges for cause. Votes Required for Conviction and Acquittal Panel Size - 2/3 - Votes for Conviction - Votes for Acquittal 12 - 7.99 - 8 - 4 11 - 7.33 - 8 - 4 10 - 6.66 - 7 - 4 9 - 5.99 - 6 - 4 8 - 5.33 - 6 - 3 7 - 4.66 - 5 - 3 6 - 3.99 - 4 - 3 5 - 3.33 - 4 - 2 From a purely mathematical perspective, it's clear that the most favorable jury size for a court-martial is 8. At eight members, the prosecution needs to obtain 6 votes for a conviction. The defense lawyer needs 3 for an acquittal. Military judges also have wide discretion in how jury selection is conducted. A minimal written questionnaire is completed by members after they have been notified about their service. At the discretion of the trial judge, this questionnaire may be supplemented with an additional questionnaire much like what is allowed in civilian courts. The general selection procedure at trial starts with group voir dire conducted by a judge, followed by group voir dire conducted by the parties. The judge may or may not allow follow-up questioning in the group format, but individual questioning of members out of the presence of other members may occur in response to answers given during group voir dire, and in some cases, may be entirely new areas of inquiry. The basis for challenge to a member is in Rule for Courts-Martial (R.C.M.) 912 (f)(1)(A)(N). They are (a) actual bias and (b) implied bias (which is unique to the military and addresses the perceptions of fairness by outside observers of the outcome of a court-martial that included the member(s) at issue. The liberal grant mandate directs the trial judge to be generous or liberally grant the accused's challenges for cause based on actual or implied bias. However, the liberal grant mandate only applies to the accused and does not extend to challenges for cause raised by trial counsel. Here is a more detailed description of the law from one of our recent appellate briefs: “As a matter of due process, an accused has a constitutional right, as well as a regulatory right, to a fair and impartial panel.” United States v. Wiesen, 56 M.J. 172, 174 (C.A.A.F. 2001). Rule for Courts-Martial 912(f)(1)(N) states: “[a]member shall be excused for cause whenever it appears that the member . . . [s]hould not sit in the interest of having the court-martial free from substantial doubt as to legality, fairness, and impartiality.” A military judge looks to the “totality of the circumstances” of a particular case when determining member bias, actual or implied. United States v. Nash, 71 M.J. 83, 88 (C.A.A.F. 2012). “This rule encompasses challenges based upon both actual and implied bias.” United States v. Bagstad, 68 M.J. 460, 462 (C.A.A.F. 2010)(quoting United States v. Elfayoumi, 66 M.J. 354, 356 (C.A.A.F. 2008)). Actual and implied bias are “‘separate legal tests, not separate grounds for challenge.’” United States v. Briggs, 64 M.J. 285, 286 (C.A.A.F. 2007) (quoting United States v. Armstrong, 54 M.J. 51, 53 (C.A.A.F. 2000)). The court uses an objective standard to determine if implied bias exists. Wiesen, 56 M.J. at 175. “The core of that objective test is the consideration of the public’s perception of fairness in having a particular member as part of the court-martial panel.” United States v. Peters, 74 M.J. 31, __, 2015 CAAF LEXIS 143, *8 (C.A.A.F. 2015)(citing United States v. Rome, 47 M.J. 467, 469 (C.A.A.F. 1998)). “A military judge’s decision whether to grant a challenge for cause based on actual bias is reviewed for an abuse of discretion.” United States v. Leonard, 63 M.J. 398, 402 (C.A.A.F. 2006). Appellate courts defer to the military judge, “only when . . . [he] indicates on the record an accurate understanding of the law and its application to the relevant facts.” Briggs, 64 M.J. at 287 (citing United States v. Downing, 56 M.J. 419, 422 (C.A.A.F. 2002)). A military judge receives less deference “on questions of implied bias.” Bagstad, 68 M.J. at 462. Implied bias “is objectively viewed through the eyes of the public, focusing on the appearance of fairness.” United States v. Bragg, 66 M.J. 325, 326 (C.A.A.F. 2008). Qualified disclaimers of bias are insufficient to overcome a member’s apparent bias. United States v. Martinez, 67 M.J. 59, 61 (C.A.A.F. 2008). “A prospective juror's assessment of her own ability to remain impartial is irrelevant for the purposes of the [implied bias] test.” United States v. Mitchell, 690 F.3d 137, 142 (3rd Cir. 2012)(citing United States v. Torres, 128 F.3d 38, 45 (2nd Cir. 1997)). A qualified response to rehabilitative questions may raise additional doubts about a panel member’s impartiality. Nash, 71 M.J. at 99 (“While the military judge is in the best position to judge the demeanor of a member, in certain contexts mere declarations of impartiality, no matter how sincere, may not be sufficient.”) Simple “yes” or “no” answers to a military judge’s leading rehabilitative questions may not overcome the bias. See Martinez, 67 M.J. at 60-61. “In close cases, military judges are enjoined to liberally grant challenges for cause.” Id. at 61. Federal courts follow the same rule, that doubts about juror impartiality are resolved against the juror. United States v. Polichemi, 219 F.3d 698, 704 (7th Cir. 2000)(explaining that a juror who belongs to a class presumed biased “may well be objective in fact, but the relationship is so close that the law errs on the side of caution”). The liberal grant mandate is even more significant in the military context because the defense has only one peremptory challenge. United States v. Schlamer, 52 M.J. 80, 93 (C.A.A.F. 1999). A military judge has a duty to apply the “liberal grant” mandate in ruling on challenges for cause. Leonard, 63 M.J. at 402. However, merely stating the words “liberal grant mandate” on the record is not sufficient to satisfy the military judge’s duty to inquire into a member’s underlying bias. The trial judge must inquire into the facts underlying the bias. See Mitchell, 690 F.3d at 143. |

Court-Martial Defense

Know Your Rights The Court-Martial Process General Court-Martial Summary Courts-Martial Your Right to an Attorney How to Obtain Experts Right to a Speedy Trial Types of Affirmative Defenses The Military Rules of Evidence Military Motions Practice Court-Martial Consequences Sex Offender Registration Military jury voting chart of required votes for a conviction or sentence over 10 years.

Initial consultations are confidential, but do not constitute the creation of an attorney-client relationship.

|