|

The statements of an accused are excludable from a court-martial or administrative separation board if they are obtained in violation of the privilege against self-incrimination under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Article 31 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, or through the use of coercion, unlawful influence, or unlawful inducement. Mil. R. Evid. 304 (c)(3).

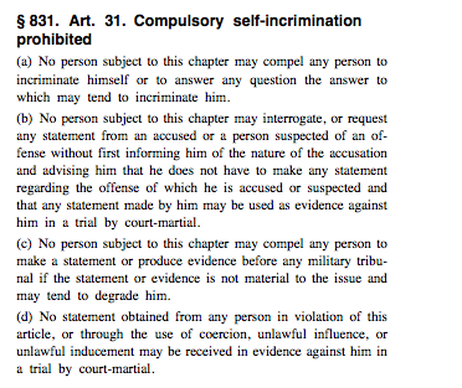

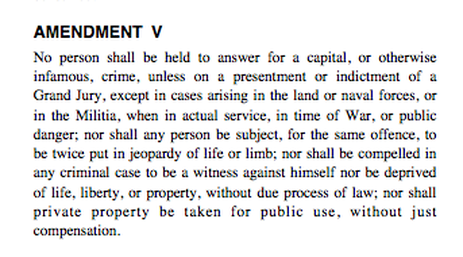

Because of the "uniquely coercive factors present in a military environment," this privilege against self-incrimination is even more highly guarded in military than in civilian contexts. United States v. Ravenel, 26 M.J. 344, 349 (C.M.A. 1988). Article 31 Sample Navy and Marine Corps Motion to Suppress Involuntary Statements Under Article 31, UCMJ Firstly, the United States Constitution and Article 31 (b) of the UCMJ require rights advisements before interrogations or requests for statements. The Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (C.A.A.F.) has repeatedly recognized that rights advisements have a particular significance in the military because the effect of “superior rank or official position upon one subject to military law, [is such that] the mere asking of a question under [certain] circumstances is the equivalent of a command.” United States v. Harvey, 37 M.J. 143 (C.M.A. 1993). Where an earlier statement was involuntary because the accused was not properly warned of his Article 31 (b) rights, the voluntariness of the second statement is determined by the totality of the circumstances. United States v. Brisbane, 63 M.J. 106, 114 (C.A.A.F. 2006). Further, Congress has enacted the exclusionary provision of Article 31 (d) as a strict enforcement mechanism to protect a service member’s Article 31 (b) rights. United States v. Swift, 53 M.J. 439, 448 (C.A.A.F. 2000). Under Article 31(b) “No person . . . may interrogate, or request any statement from, an accused or a person suspected of an offense without first informing him of the nature of the accusation . . . . “ Rule 305(c) of the Military Rules of Evidence, further clarifies, “A person subject to the code who is required to give warnings under Article 31 may not interrogate or request any statement from an accused or a person suspected of an offense without first: (1) [i]nforming the accused or suspect of the nature of the accusation . . . .” The case law reiterates, “The accused must be made aware, however, of the general nature of the allegation. The warning must include the area of suspicion and sufficiently orient the accused toward the circumstances surrounding the event.” United States v. Huelsman, 27 M.J. 511, 513 (A.C.M.R. 1988) (citing United States v. Schultz, 19 U.S.C.M.A. 31, 41 C.M.R. 31 (C.M.A. 1970); United States v. Reynolds, 16 U.S.C.M.A. 403, 37 C.M.R. 23 (C.M.A. 1966)). See also United States v. Pipkin, 58 M.J. 358, 360 (C.A.A.F. 2003) (quoting United States v. Simpson, 54 M.J. 281, 284 (C.A.A.F. 2000)) (holding that the suspect has a right to know the general nature of the allegation). In Huelsman, the court held the individual’s statements made in regards to possession and distribution of marijuana was inadmissible because even though he was advised of his rights in regards to the larceny charge, he was not informed that he was suspected of possession and distribution. United States v. Redd, 67 M.J. 581, 588 (A.C.C.A. 2008) (citing Huelsman, 27 M.J. at 513). If the nature of the charge is not explicit, confessions are voluntary if the individual has constructive notice of the charge. That is not the case here. United States v. Annis, 5 M.J. 351, 352-53 (C.M.A. 1978). In Reynolds the airman’s statements were involuntary because although he knew he was suspected of wrongful leave, he was not aware of the wrongful appropriation charge. United States v. Piazza, No. 200301263, 2005 CCA LEXIS 370, at *7 (N-M.C.C.A. Nov. 22, 2005) (citing United States v. Reynolds, 16 C.M.A. 403, 405 (C.M.A. 1966)). The Article 31(b) warning requirements can apply to civilian investigators working with the military. Mil. R. Evid. 305(c) applies to civilians (1) “[w]hen the scope and character of the cooperative efforts demonstrate that the two investigations merged into an invisible entity” and (2) “when the civilian investigator acts in furtherance of any military investigation, or in any sense as an instrument of the military[.]” United States v. Payne, 47 M.J. 37, 42 (C.A.A.F. 1997) (citing United States v. Quillen, 27 M.J. 312, 314 (C.M.A. 1988). Joint Civilian and Military Investigations In determining whether two investigations have merged into one entity, “military courts consider the purpose of each of the two investigations and whether [the agencies] act independently.” United States v. Lonetree, 35 M.J. 396, 404 (C.M.A. 1992). In Lonetree, civilian intelligence agents investigating classified information disclosure obtained admissions from the accused. Id. at 398. After obtaining the statements from the accused, the civilian intelligence agents provided this information to the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS). Id. NCIS opened their own investigation. Id. NCIS then interviewed the accused under rights advisement and used information previously provided by the intelligence agents. Id. The court determined that this level of cooperation did not implicate Article 31 for the intelligence agents, and they did not have to read the accused his rights at any time. In determining whether a civilian investigator is acting as an “instrument of the military,” a key consideration is whether there is any “degree of control” by the military over the civilian investigator. Payne, 47 M.J. at 43. There must be more than a mere cooperative relationship.[1] In Payne, the court found that a civilian polygraph examiner was not required to issue article 31(b) rights. 47 M.J. at 43. There was no cooperation or coordination between CID and DIS, beyond a preliminary release of records. Id. The DIS (civilian) and CID investigations in that case had different purposes and scopes. Id. Accordingly, with minimal coordination, the DIS agents were not acting as instruments of the military. Id. The Fifth Amendment and Miranda Warnings The government may not use statements stemming from the custodial interrogation of the accused unless it demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the privilege against self-incrimination. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 444 (1966). The courts have defined custodial interrogation as “questioning initiated by law enforcement officers after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way.” Id. When there is custodial interrogation, the United States Supreme Court has set out the procedural safeguards required. Id. At a minimum, “[p]rior to any questioning, the person must be warned that he has a right to remain silent, that any statement he does make may be used as evidence against him, and that he has a right to...an attorney.” Id. If there is custodial interrogation and the procedural safeguards, or warnings, are not issued, the confession or sworn statement is not admissible. Id. In determining whether a custodial interrogation has taken place, “a court must examine all of the circumstances surrounding the interrogation.” Stansbury v. California, 511 U.S. 318, 322 (1994). The court determines the existence of a custodial interrogation based on an objective standard, or “how a reasonable man in the suspect’s position would have understood his situation.” Berkemer v. McCarty, 468 U.S. 420, 442 (1984). Determinations of when an accused is subjected to a custodial interrogation are based on the totality of the circumstances and include factors such as voluntariness, whether the accused was a suspect at the time, and whether he was under guard during the interview. United States v. Schneider, 14 M.J. 189, 195 (C.M.A. 1982). In California v. Beheler, the suspect called the police to report a homicide that he was involved with. 463 U.S. 1121, 1122 (1983). He voluntarily accompanied police to the police station for questioning. Id. The police never issued his Miranda rights. Id. He gave a brief interview, less than 30 minutes, and then left freely. Id. The Court found that Miranda warnings were not required. Id. The Court noted that although the circumstances of each case must influence a determination of whether a suspect is "in custody," the standard is actual custody or restraint that is the functional equivalent of formal arrest. Id. at 1125. [1] See Lonetree, 35 M.J. at 404 (minimal cooperation was found where civilian investigators had no contact with NCIS prior to the interview where unadvised statements were obtained); Quillen, 27 M.J. at 314-15 (civilian was found to be an instrument of the military where the civilian was employed by the military for security reasons). |

Court-Martial Defense

Know Your Rights The Court-Martial Process General Court-Martial Summary Courts-Martial Your Right to an Attorney How to Obtain Experts Right to a Speedy Trial Jury Selection in the Military The Military Rules of Evidence Military Motions Practice Court-Martial Consequences Sex Offender Registration Initial consultations are confidential, but do not constitute the creation of an attorney-client relationship.

|